A laminated shingle is a multi-layer composite roofing material engineered to resist environmental forces through the specific physical properties of its bonded components. Its primary function is to serve as the top covering of a building, providing absolute protection against rain, snow, sunlight, temperature extremes, and wind. The lamination process creates a shingle with greater mass, dimensionality, and structural integrity than a monolithic, single-piece shingle. Understanding the physics of this construction is the first step in eliminating the chaos and unpredictability common in roofing projects.

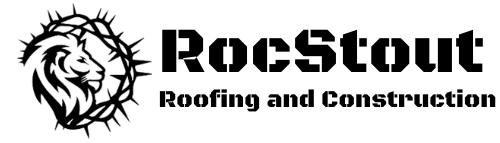

Anatomy of a Laminated Shingle: A Multi-Layer System

A laminated, or architectural, shingle is not a single material. It is a system of distinct layers, each engineered to perform a specific function. The failure of any one layer compromises the entire system. We view each component as a critical point of quality control, essential for a predictable outcome.

The outermost barrier, providing UV radiation defense, impact resistance, and color.

The primary waterproofing agent that repels rain and snow, protecting the core.

The structural backbone, providing tensile strength and dimensional stability.

The thermally activated adhesive that bonds shingle courses together against wind uplift.

The Fiberglass Mat: Engineering Core Structural Integrity

The core of an asphalt shingle is the fiberglass reinforcing mat. This is the shingle’s skeleton. It is a non-woven web of glass fibers bonded together, providing high tensile strength and dimensional stability. Its function is to hold the asphalt and other components in a fixed, predictable shape. A shingle without a high-quality fiberglass mat is prone to tearing during installation and cracking from thermal expansion and contraction over its service life. This material choice is a primary reason for the superior fire resistance of modern shingles compared to older organic-felt based materials.

Asphalt (Bitumen) Layers: The Primary Barrier Against Rain & Snow

Weathering-grade asphalt, or bitumen, is saturated into the fiberglass mat. This layer performs the most critical function of any roof covering: it makes the shingle waterproof. The asphalt creates an impermeable barrier against rain and snow. Fillers such as ground limestone are added to the asphalt to increase its bulk, improve its fire resistance, and enhance its durability under extreme temperatures. A failure in the asphalt layer, often seen as cracking or blistering, directly exposes the underlying roof structure to water intrusion.

Ceramic Granules: Your First Line of Defense Against Sunlight & Impact

The visible surface of the shingle is coated with a dense layer of ceramic-coated mineral granules. These granules serve two primary physical purposes. First, they shield the asphalt layer from ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Persistent UV exposure photo-oxidizes asphalt, making it brittle and causing it to fail prematurely. Second, the granules provide impact resistance against hail and debris. Their hardness and distribution are engineered to dissipate kinetic energy. They are also the source of the shingle’s color and can be formulated to reflect solar radiation, contributing to the energy efficiency of the building envelope.

Sealant Strip Analysis: The Key to Wind Uplift Protection

Each shingle contains a strip of thermally activated asphalt sealant. After installation, solar radiation heats this adhesive, bonding the shingle course to the one below it. This creates a monolithic, unified surface. The physics are simple: this bond must be stronger than the force of wind uplift acting on the edge of the shingle. The mass, chemical composition, and placement of this sealant strip are critical variables that directly correlate to the shingle’s certified wind resistance rating. Inadequate sealing is a leading cause of catastrophic roof failure during high-wind events.

The Lamination Process: How Dimensionality Creates Durability

Lamination is the manufacturing process that separates a basic 3-tab shingle from a high-performance architectural shingle. It is the physical fusion of multiple shingle layers into a single, thicker, and more robust unit. This process is not merely for aesthetics; it is fundamental to the shingle’s durability and longevity.

Structural Comparison: Two-Piece Laminated vs. Single-Piece Shingles

A standard 3-tab shingle is a single, monolithic piece of asphalt-coated fiberglass cut to resemble three separate shingles. A laminated architectural shingle consists of two or more pieces physically bonded together. This two-piece construction provides a measurable increase in durability.

| Attribute | Laminated (Architectural) Shingle | 3-Tab Shingle |

|---|---|---|

| Construction | Two or more layers fused together | Single monolithic layer |

| Weight & Mass | Significantly heavier; better resistance to uplift | Lighter; more susceptible to wind damage |

| Dimensionality | Thicker profile creates deep shadow lines | Flat, uniform appearance |

| Typical Wind Warranty | 110-130 mph | 60 mph |

The additional thickness and irregular profile of the laminated shingle disrupt airflow, reducing the negative pressure that causes wind uplift. The increased mass also requires more force to lift the shingle. This results in a product that fundamentally outperforms its single-layer predecessor.

Thermal Bonding: Fusing Layers to Prevent Delamination

During manufacturing, the separate layers of a laminated shingle are fused using heat and pressure. This thermal bonding process is critical. If the bond is incomplete or weak, the shingle will delaminate. Delamination occurs when the layers separate, trapping water and wind, which rapidly accelerates the failure of the entire roof covering. Consistent manufacturing quality control during this stage is non-negotiable for ensuring long-term performance.

Performance Metrics: Translating Construction to All-Weather Protection

The physical construction of a laminated shingle translates directly to quantifiable performance metrics. These are not marketing terms; they are standardized tests that define a shingle’s capacity to protect your home from wind, fire, and solar energy. For an organized homeowner, these metrics provide the data needed to make an informed decision.

Wind Resistance Ratings: A Function of Nailing Zone & Sealant Mass

Wind resistance is tested under ASTM D7158. Shingles are assigned a class (e.g., Class H for 150 mph) based on their ability to resist uplift. This performance is a direct result of two design factors: the sealant strip’s adhesive strength and the integrity of the reinforced nailing zone. The laminated design allows for a wider, more robust nailing zone, which reduces the chance of fasteners pulling through the shingle under high stress—a common failure point in the chaos of a storm.

Fire Resistance: Understanding Class A Shingle Construction

The highest fire resistance rating for a roof covering is Class A, tested under UL 790. Laminated shingles achieve this rating primarily due to the inert fiberglass mat at their core. Unlike older organic felt mats, fiberglass does not burn or support combustion. The dense layer of mineral granules on the surface also helps to insulate the asphalt from external flame sources. This construction is a code requirement in many areas and a fundamental safety specification.

Impact on Temperature: How Granule Color Affects Solar Reflectance

The granules are not just for protection; they also manage solar energy. Cool roof shingles use specially coated granules designed to reflect a higher percentage of infrared radiation. This property is measured by the Solar Reflectance Index (SRI). A higher SRI value means the roof surface stays cooler, reducing heat transfer into the building and lowering cooling costs. This turns the shingle from a passive barrier into an active component of the home’s energy management system.

The RocStout Method: Executing Flawless Shingle Construction

Understanding the physics of a shingle is irrelevant if its installation is flawed. The typical roofing experience is defined by chaos: missed deadlines, imprecise work, and poor communication. Our entire business model is built as the antidote to that chaos. We translate the engineered precision of the shingle to the installation process itself.

Material Verification: Our Protocol for Vetting Shingle Quality

Our process begins before a single bundle arrives at your property. We verify lot numbers and manufacturing dates to ensure material consistency. We inspect bundles for signs of shipping damage or manufacturing defects that could lead to delamination or other premature failures. We see the materials not as commodities, but as components in a complex system that must meet exact specifications to function predictably.

Installation as a System: Eliminating Chaos and Variables

We install a roofing system, not just shingles. This means every component—underlayment, starter strips, flashing, ventilation—is selected and installed according to a strict, documented process. You will have a dedicated project manager, your single point of contact, who provides frequent, clear updates. Our work is systematic and transparent. There are no surprises, because every variable is controlled through rigorous project management.

A Note on Price: We Prioritize Predictability Over Low Bids

We are not the right contractor for every project. If your primary decision criterion is finding the lowest possible price, we will respectfully decline the opportunity to bid. Our process is intentionally meticulous, our standards are uncompromising, and our communication is constant. This level of control and predictability has a cost, and it is not compatible with a race-to-the-bottom pricing model. Our clients are organized professionals who understand that the true cost of a project includes the stress, disorganization, and risk associated with a chaotic, low-bid process. They are investing in a predictable outcome, not just a roof covering.