A balanced attic ventilation system is an engineered construction of intake and exhaust vents designed to manage temperature and moisture within the attic space through continuous, passive airflow. This system is a critical component of your home’s roof, which functions as the top covering of the building to provide protection against environmental factors like rain, snow, and extreme temperatures. An improperly designed system compromises this protective function, leading to predictable and costly failures. Our focus is on engineering predictable outcomes. If your primary goal is securing the lowest bid, we are not the right company for your project. We serve meticulous homeowners who value a process that eliminates chaos and guarantees performance.

The Core Principle: A System for Managing Temperature and Moisture

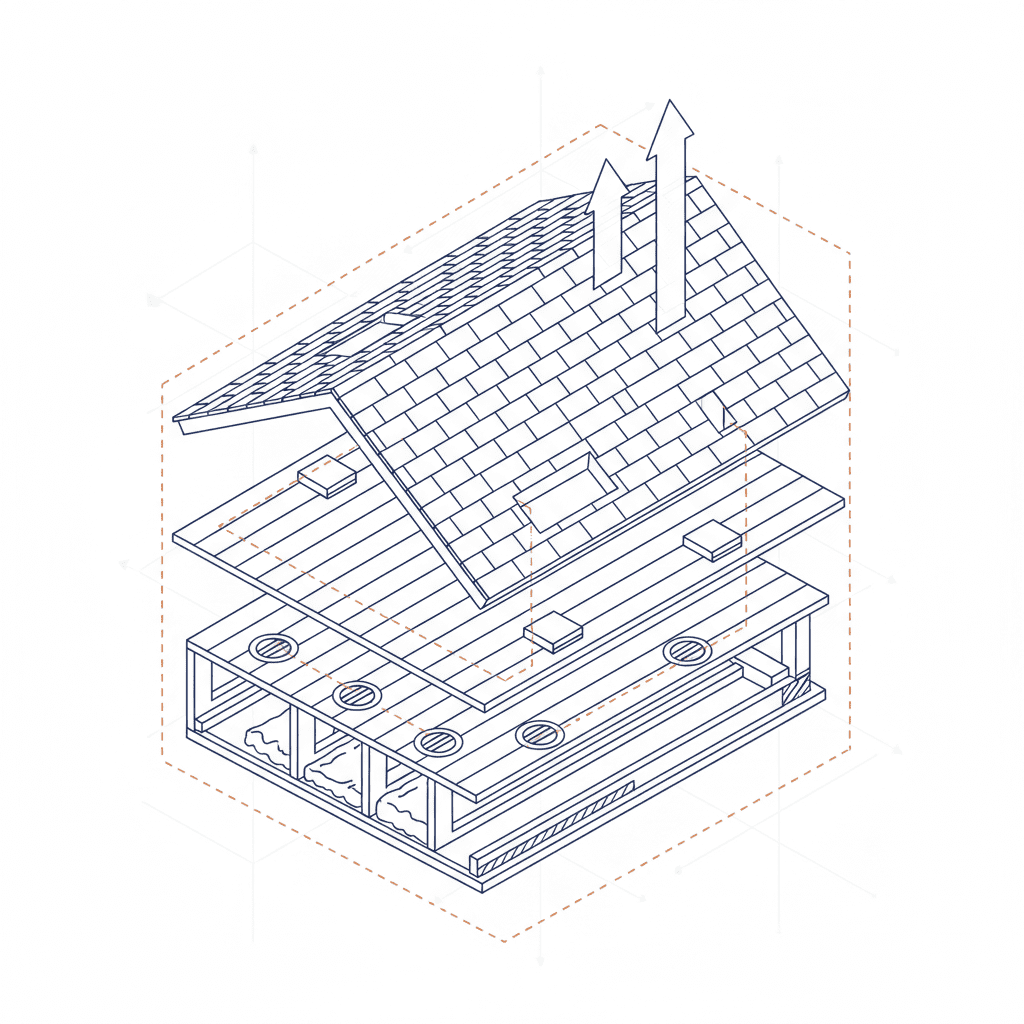

An attic ventilation system is not a collection of parts; it is an integrated system governed by building science. Its two primary functions are temperature regulation and moisture control. In the summer, it expels super-heated air that would otherwise radiate into your living space and prematurely age your shingles. In the winter, it removes warm, moist air generated within the home before it can condense on cold roof sheathing, which leads to mold, rot, and compromised insulation. A correctly balanced system protects the entire roof structure, from the deck to the top covering.

Intake vs. Exhaust: The Physics of Passive Airflow

A passive ventilation system operates without mechanical assistance, relying on two fundamental physics principles: thermal buoyancy (the stack effect) and wind pressure. The stack effect is the process where cooler, denser air enters through low intake vents (typically soffit vents), is warmed by the sun-heated roof deck, and rises as it becomes less dense. This warm, buoyant air then exits through high exhaust vents (typically a ridge vent). This creates a continuous, passive cycle of airflow that removes heat and moisture. A properly engineered system ensures this airflow path is unobstructed and balanced, preventing system failure.

Calculating Net Free Area (NFA): The 1/300 Rule Explained

Net Free Area (NFA) is the total unobstructed area through which air can pass through a vent. It is the industry standard for measuring ventilation capacity. Building codes, based on extensive research, provide a clear standard for calculating the required NFA: the 1/300 rule. This rule states that a minimum of 1 square foot of NFA is required for every 300 square feet of attic floor space. A critical component of this rule is the balance: 50% of the NFA must be allocated to intake ventilation and 50% must be allocated to exhaust ventilation. This precise 50/50 balance is non-negotiable for system performance.

Consequences of Imbalance: Predictable System Failure Modes

An imbalanced ventilation system is a failed system. The consequences are not random; they are predictable outcomes rooted in physics. When exhaust NFA exceeds intake NFA, the system becomes ‘starved’ for air and can pull conditioned air from the living space or draw weather into the attic. When intake exceeds exhaust, airflow stagnates, trapping heat and moisture. Common failure modes include:

- Ice Dams: In cold climates, trapped attic heat melts snow on the roof. This water refreezes at the colder eaves, forming dams that force water under shingles, causing leaks and structural damage.

- Mold Growth: Trapped moisture from daily living (showers, cooking) condenses on the cold underside of the roof deck, creating an ideal environment for mold and mildew.

- Roof Sheathing Rot: Persistent condensation saturates the OSB or plywood roof deck, causing it to lose structural integrity, delaminate, and rot.

- Shingle Deterioration: Extreme heat buildup in an unventilated attic essentially ‘cooks’ asphalt shingles from below, accelerating the loss of protective granules and causing premature cracking and failure.

Analyzing Ventilation Components as an Integrated Construction

The selection and placement of ventilation components are not aesthetic choices. They are engineering decisions that determine the efficacy of the entire roof system. A methodical approach requires understanding how each component functions within the whole. The typical industry chaos of mixing and matching vents based on availability or ease of installation is a direct path to system failure.

Intake Ventilation Types: Soffit, Drip-Edge, and Fascia Vents

Intake vents are installed low on the roof or in the eaves to allow cool, fresh air to enter the attic.

| Vent Type | Description | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Soffit Vents | Installed in the soffit (the underside of the roof overhang). Provides the most balanced and evenly distributed air intake. | Homes with adequate soffit/eave space. The gold standard for passive systems. |

| Drip-Edge Vents | Installed at the roof edge. A viable option when soffits are non-existent or too narrow for standard vents. | Homes with little to no roof overhang. Requires precise installation to prevent water infiltration. |

| Fascia Vents | Installed on the vertical fascia board. Another alternative for homes without soffits. | Requires careful calculation to ensure adequate NFA and proper weather protection. |

Exhaust Ventilation Types: Ridge, Gable, and Static Vents

Exhaust vents are installed at or near the highest point of the roof to allow warm, moist air to escape the attic.

| Vent Type | Description | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ridge Vent | Installed along the entire peak (ridge) of the roof. Provides the most effective and evenly distributed exhaust. | The preferred exhaust method for gable roofs. Creates a perfect pairing with soffit intakes. |

| Static Vents (Box Vents) | Individual, passive vents installed near the ridge. They rely on wind and convection. | Can be effective on certain roof designs, but require multiple units and careful placement to achieve adequate NFA. |

| Gable Vents | Louvered vents installed in the gable walls at the ends of the attic. | An older technology that relies heavily on wind pressure and is often insufficient as a primary exhaust system. |

System Chaos: The Technical Failures of Mixing Vent Types

Combining different types of exhaust vents—for example, a ridge vent with gable vents—is a critical design flaw. It creates chaos in the airflow dynamics. Air will always follow the path of least resistance. A gable vent, being lower than the ridge vent, can act as a secondary intake vent. This ‘short-circuits’ the system. Air enters the gable vent and exits the nearby ridge vent, leaving the lower two-thirds of the attic and the critical soffit intake vents completely stagnant. This stagnation guarantees moisture buildup and heat accumulation, defeating the purpose of the entire system.

The Fallacy of Powered Vents in a Passive Roof System

A powered attic vent (PAV) is often sold as a solution for a hot attic. In reality, it is a mechanical patch for a poorly designed passive system. A PAV aggressively depressurizes the attic, creating a strong negative pressure. Because it moves air much faster than passive intake vents can supply it, the fan will pull air from the easiest available sources. This often includes pulling conditioned (and expensive) air from your living space through ceiling light fixtures and other gaps. In homes with combustion appliances, this can even cause dangerous backdrafting of carbon monoxide. A properly designed passive system requires no electricity, has no moving parts to fail, and operates silently and efficiently year-round.

Impact of Ventilation on Roof Materials and Structural Longevity

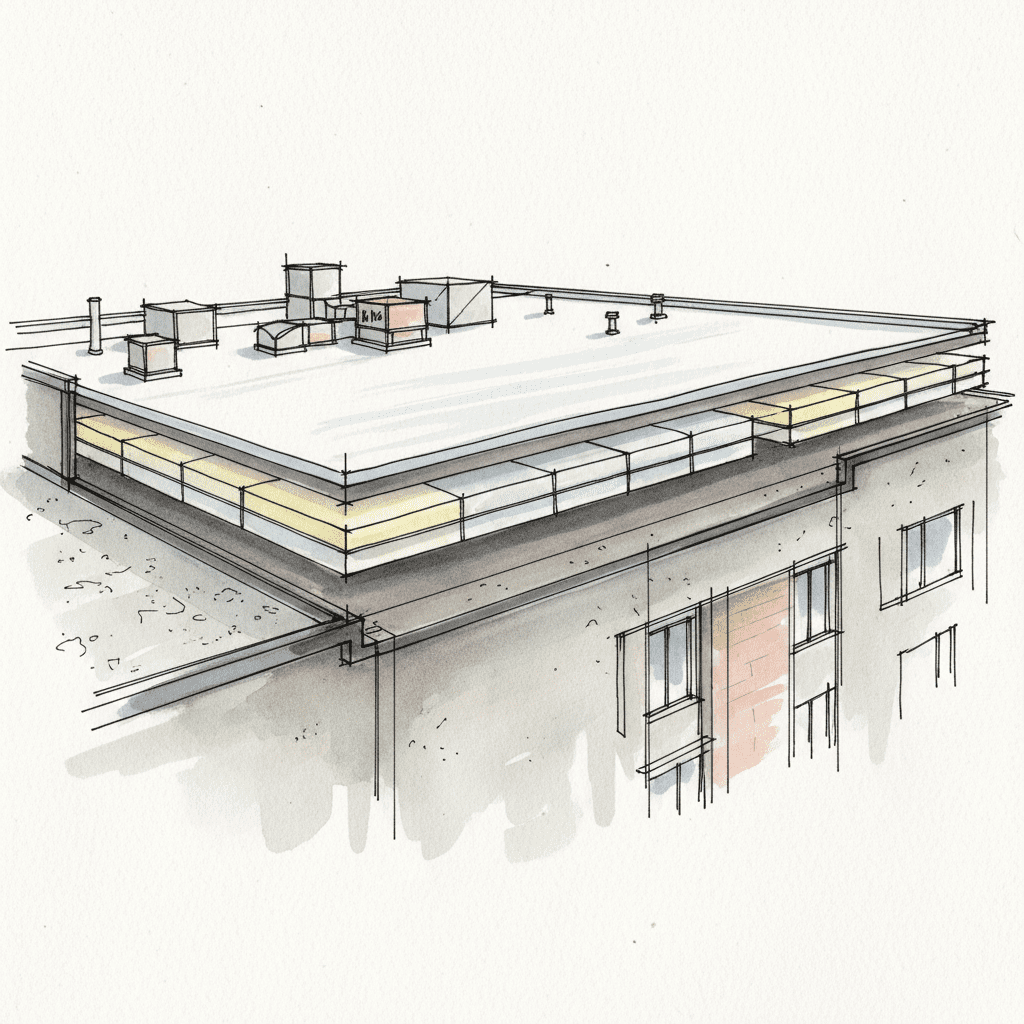

Proper ventilation is not an accessory; it is a fundamental requirement for protecting your roofing investment. It directly influences the lifespan of every material from the structural sheathing to the visible top covering of shingles. Viewing ventilation as optional is a financially indefensible position.

Protecting the Roof Deck from Moisture Degradation

The roof deck, typically constructed from Plywood or Oriented Strand Board (OSB), is the structural foundation of your roof. It must remain dry to maintain its strength. A poorly ventilated attic allows moisture-laden air to condense on the cold underside of the deck during winter. This chronic dampness leads to wood rot, delamination, and a loss of fastener-holding capacity. A sagging roofline is a clear indicator of a long-term ventilation failure that has compromised the deck.

Maximizing Shingle Lifespan by Mitigating Extreme Temperatures

Asphalt shingles are designed to withstand sunlight and weather from above. They are not designed to be baked from below by a super-heated attic. Extreme thermal cycling caused by trapped heat accelerates the degradation of the asphalt, causes shingles to become brittle, and leads to granule loss. This premature aging not only shortens the life of your roof but also voids most manufacturer warranties, which explicitly require adherence to building code ventilation standards.

Preserving Insulation R-Value and Home Energy Efficiency

Attic insulation functions by trapping air, which slows the transfer of heat. When insulation becomes damp from attic condensation, it compresses and loses its trapped air pockets. This dramatically reduces its R-value, or thermal resistance. Damp insulation is ineffective insulation. This forces your HVAC system to work harder to maintain a stable temperature, directly increasing your heating and cooling costs. Proper ventilation protects your insulation, ensuring it performs as specified and contributes to your home’s overall energy efficiency.

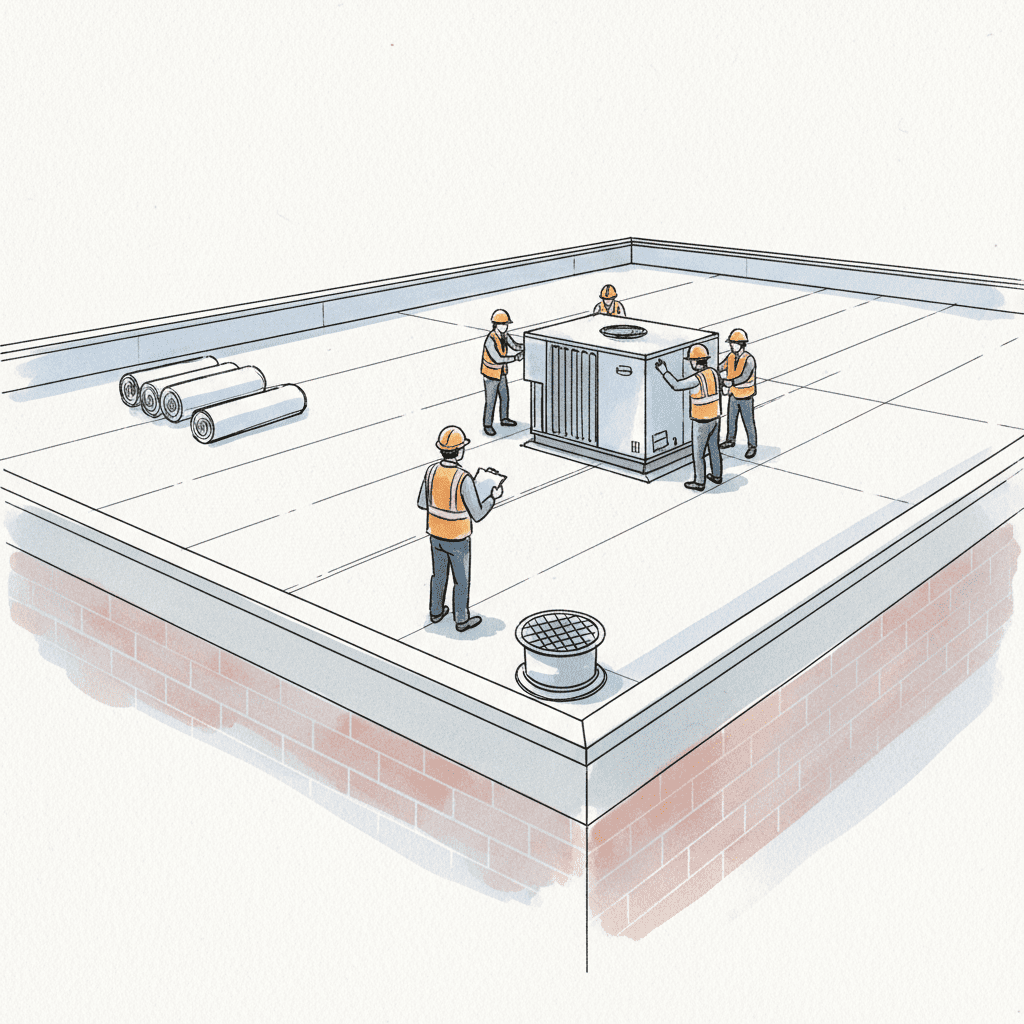

Our Process: A Methodical Approach to Ventilation Design

The standard roofing experience is defined by chaos, estimates based on guesswork, and a lack of accountability. We have engineered a different approach. Our process is methodical, transparent, and designed to deliver a predictable, stress-free outcome. It is the only sane way to manage a complex construction project on your most valuable asset.

We do not guess. We measure the attic floor space, inspect existing insulation and airflow pathways, and identify any structural impediments. We then perform a precise Net Free Area calculation based on the 1/300 rule to determine the exact ventilation requirements for your home.

Based on the data from the audit, we design a balanced system. This includes specifying the exact type, quantity, and placement of intake and exhaust vents to achieve the target 50/50 NFA balance. This plan is documented in a detailed scope of work, ensuring complete transparency.

Our certified installers execute the plan with precision. We ensure soffit intakes are not blocked by insulation and that ridge vents are installed with the correct air gap. Upon completion, we verify that the system is functioning as designed. This quality assurance step is non-negotiable and guarantees performance.

Technical FAQ for the Analytical Homeowner

For the homeowner who values data and clarity, here are direct answers to common technical questions.

Is a Ventilation System Upgrade Required with a New Roof?

Almost always. The vast majority of existing homes have ventilation systems that are inadequate, imbalanced, or non-compliant with current building codes. Installing a new, warrantied roof on top of a failed ventilation system is a technical and financial contradiction. A roof replacement is the ideal and most cost-effective time to engineer and install a correct, balanced system that protects your new investment and validates its warranty.

How Does Climate Zone Affect Ventilation Requirements?

Climate zone significantly impacts ventilation strategy. Colder zones with heavy snow load require robust systems to combat ice dams and manage large temperature differentials. Hot, humid climates demand high airflow to expel moisture and mitigate extreme attic temperatures. Some specific building codes, like the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), may allow for a 1/150 rule in certain roof assemblies, but the 1/300 rule with a 50/50 balance remains the universal standard for ensuring performance across all zones.

What Are the Risks of Over-Ventilating an Attic?

The primary risk is not necessarily ‘too much’ ventilation, but rather an imbalance in the NFA ratio. The most common issue with ‘over-venting’ is installing an excessive amount of exhaust ventilation without a corresponding increase in intake. This starves the system, creating negative pressure that can draw wind-driven rain or snow into the attic through the vents. The goal is not maximum ventilation; the goal is a balanced system engineered to the specific NFA requirements of your attic.